Although the political agreement between SDA and HDZ, reached on June 18th this year, will enable the holding of elections in Mostar and thus break the decade-long blockade of the election process, many experts are pessimistic that something more significant will change in this city. Senior Associate of the Democratization Policy Council Bodo Weber says that the agreement reached is not in for the future of Mostar or the whole of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He spoke for Interview.ba about why the international community agreed to an agreement that suits only two parties, what will happen if the national parties win a 2/3 majority, why Izetbegović gave in to Čović, and whether reforms to the BiH Election Law can happen at the time specified in this agreement.

IN DECEMBER, THE PEOPLE OF MOSTAR CHOOSE BETWEEN: Killing the City of Mostar or the continuation of its dysfunctionality, but which at least leaves a chance for some future reform of city institutions, ie. the political system of the city of Mostar – when the international community grapples.

INTERVIEW: Why did the international community agree to the SDA-HDZ “political agreement” on holding elections in Mostar in a form that best suits these parties?

WEBER: In the history of Western politics, ie. Weaknesses and indecisions of that policy for the last decade and a half, the Mostar agreement represents one of its lowest points. After a decade of international resistance to Čović’s lobbying that “Croats must be given something”, behind which stands nothing but a third entity project through changes to the electoral system, which serve neither Bosnian Croats nor BiH as a whole, but only the concept of “constituent ruling parties”, the West gave in for the first time. Unfortunately, what makes this precedent even worse, it seems that it is not the result of a new policy of the West, but was created in the absence of any EU and US policy towards BiH, ie the political will to seriously deal with Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Mostar agreement is the result of the engagement of several ambassadors in Sarajevo outside their capitals, which was created for quite personal, mostly careerist reasons.

INTERVIEW: How exclusive is this “political agreement” when it comes to other political options, given the fact that we know that 13 councilors are elected from the civic list and another 22 from six constituencies (which are based on ethnicity)?

WEBER: Deleting the balance of elections from the civic list and constituencies due to the dominance of elected councilors from those six constituencies, along with removing the central city zone, is the best proof of the essence of this agreement between HDZ and SDA: abuse of the European Court of Human Rights for the sake of ethnic-territorialization of the city of Mostar. The court did not criticize this balance, but only the violation of the principle of one man, one vote. The existing balance of electoral lists was in fact an attempt to strike a balance between ethnic and civic principles.

INTERVIEW: Although the elections in Mostar will revive democracy in terms of the right of citizens to vote and be elected, many are afraid that if the national parties in this city win votes, they will re-establish a system of government that will only benefit them, such as was the case in the last 12 years. How certain is it that something like this will happen?

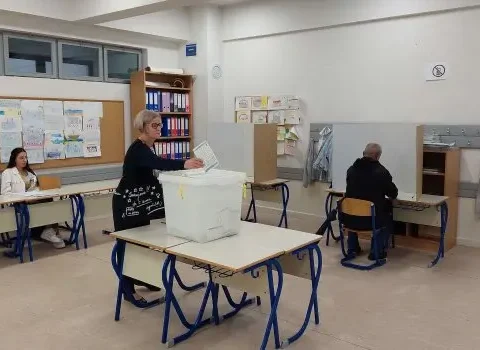

WEBER: Democracy will not be revived in Mostar. Democracy is much more than a mere form, as, in an act of voting, there must be a choice to have democratic elections. The upcoming elections are existential but of a pre-political and pre-democratic character. Citizens have a chance to thwart the HDZ and SDA plans by preventing a two-thirds majority of the two parties in the future city council. This act of resistance means that with their vote, the citizens oppose the parties that hold all the levers of power and the economy in their hands, and against the international community, which has unfortunately proved to be ignorant.

INTERVIEW: If SDA and HDZ have “stitched” this political agreement according to their wishes, then what can be expected if they have the opportunity to pass their statute and elect a mayor?

WEBER: Representatives of the two parties announced after signing the Mostar agreement that they would turn urban areas into six de facto monoethnic, realistic centers of power, and thus kill a unique city, turning city-level political institutions into ikebana. If, on the other hand, they do not get a two-thirds majority, I predict that the city will remain as dysfunctional as it has been so far with the old statute and without elections. Therefore, the citizens of Mostar in December can vote on a choice between killing the City of Mostar or continuing its dysfunctionality, but which at least leaves a chance for some future real reform of city institutions, ie. political system of the city of Mostar – when the international community grapples.

INTERVIEW: Maybe the international community was thinking of a scenario like this when they were photographed smiling behind the signatories? And did Bakir and Covic deceive the international representatives?

WEBER: I am afraid that the “international community” did not think anything, but that the support for the Mostar agreement is actually an indicator and the result of the lack of political will to seriously deal with BiH. This is already shown by the fact that the agreement on Mostar is fundamentally contrary to the Opinion of the European Commission from May last year, which in the reform conditions regarding constitutional reforms clearly indicated the principles that the constitutional reform of post-Dayton BiH must follow in order to one day become a member of the European Union: “significant restrictions on the ethnic principle of division of powers and institutions, which so far only serve the policy of interethnic fear and patronage of the ruling parties.”

INTERVIEW: Since you are following the events around Mostar, Izetbegović stated only a few days ago that he should start agreements with Čović on changes to the Election Law. It is now September, it is an election year, how realistic is it that something like this will happen within the time specified in the agreement?

WEBER: There is nothing from the implementation of the agreement on changing the BiH Election Law. It was not possible to find an agreement on the entire complex for more than a decade outside the framework of a comprehensive reform of the constitutional order of BiH, and in the absence of the principled policy of the West, so it will not be realized in less than half a year. This was probably clear from the day of signing. However, significant in this context, what will remain of the agreement, which will go down in history as all previous letters of intent, is that Bakir Izetbegović and SDA legitimized the third entity project for the first time by signing the “legitimate political representation of the constituent peoples.”

INTERVIEW: Why did Bakir Izetbegović, within the framework of this agreement, give in to Čović when it comes to changes to the BiH Election Law?

WEBER: That is a question for him and his party.

INTERVIEW: Many political analysts believe that the Constitution of FBiH and BiH was violated by deciding on the two parties in the City of Mostar exclusively, ie two constituent peoples, and what is with the third constituent people in this entity, why it is not included in the negotiations and why Milorad Dodik kept silent on this whole affair?

WEBER: “Constituent parties” such as HDZ and SDA do not care about the fate of the Serbian people in the Federation, or even the constitutive “principle” if it does not serve their interests. The same goes for Milorad Dodik, especially for him.

INTERVIEW: Does Mostar’s “political agreement” have a future?

WEBER: The Mostar agreement does not serve in favor of the future, neither for Mostar nor for BiH. How much of a future does this backward project have, we will see in the December elections, that is whether the two parties will win a two-thirds majority or not.